A working understanding of statistical methodology is helpful to feel confident about interpreting experiment results. For those without prior experience, this overview explains everything you need to know in layperson's terms. For those with some statistics experiments, this overview documents our methodology and assumptions.

Experiments use Bayesian statistics to determine whether a given variant performs better than the control. It quantifies win probabilities and credible intervals, helps determine whether the experiment shows a statistically significant effect, and enables you to:

- Check results at any time without statistical penalties.

- Get direct probability statements about which variant is winning.

- Make confident decisions earlier with accumulating evidence.

This contrasts with Frequentist statistics, which requires you to predefine sample sizes and prevents you from updating probabilities as new data arrives.

Example Bayesian analysis

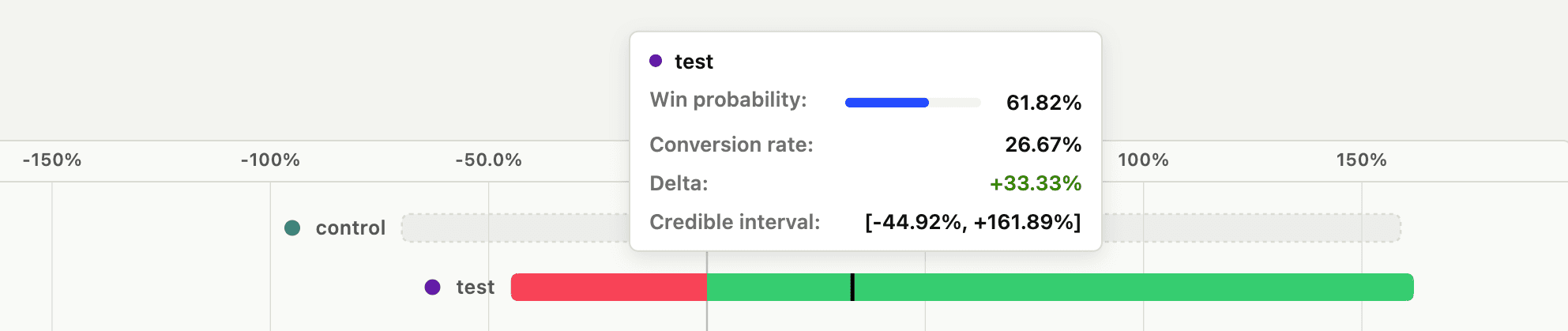

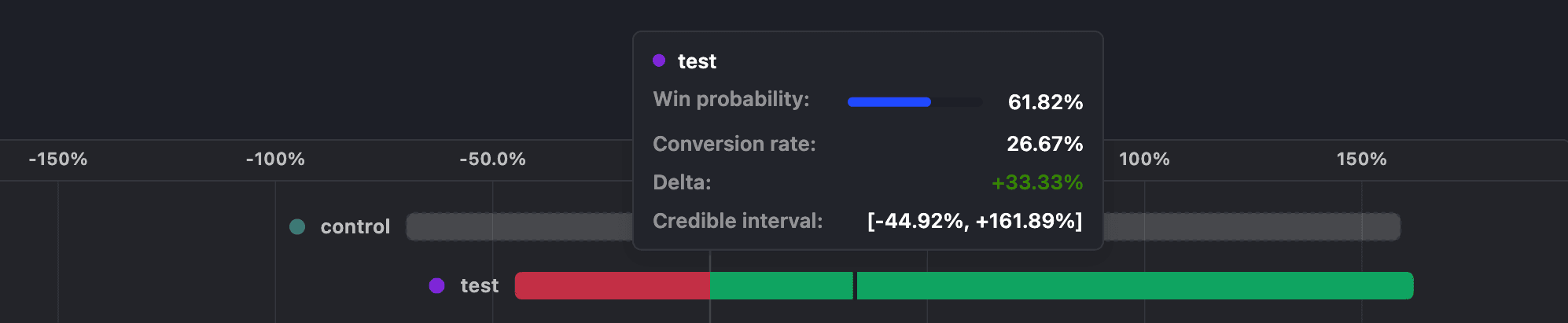

Say you started an experiment a few hours ago and see these results:

- 2 in 8 people in the control group complete the funnel = 20% success rate.

- 4 in 11 people in the test variant group complete the funnel = 26.67% success rate.

- The control variant has a 38.18% probability of being better and the test variant has a 61.82% probability of being better.

- The control variant shows a credible interval of [-69.89%, 158.88%] and the test variant shows a credible interval of [-44.92%, 161.89%].

The first two values are pure math: dividing the number of successes by the total number of users gives us the raw success rates. It's not enough to just compare these conversion rates, however.

The last two values are derived using Bayesian statistics and describe our confidence in the results. The win probability tells you how likely it is that a given variant has the highest conversion rate compared to all other variants in the experiment. The credible interval tells you the range where the true conversion rate lies with 95% probability. It is displayed relative to the control conversion rate, which makes it easier to understand the likelihood of a variant being better than the control (e.g. the test variant performs somewhere between 69.89% worse and 158.88% better than the control).

Importantly, even though the test variant is winning with a 61.82% probability of being better, it doesn't clear our threshold of 90% or greater win probability to be a statistically significant conclusion. This uncertainty is also demonstrated with the amount of overlap in the credible intervals.

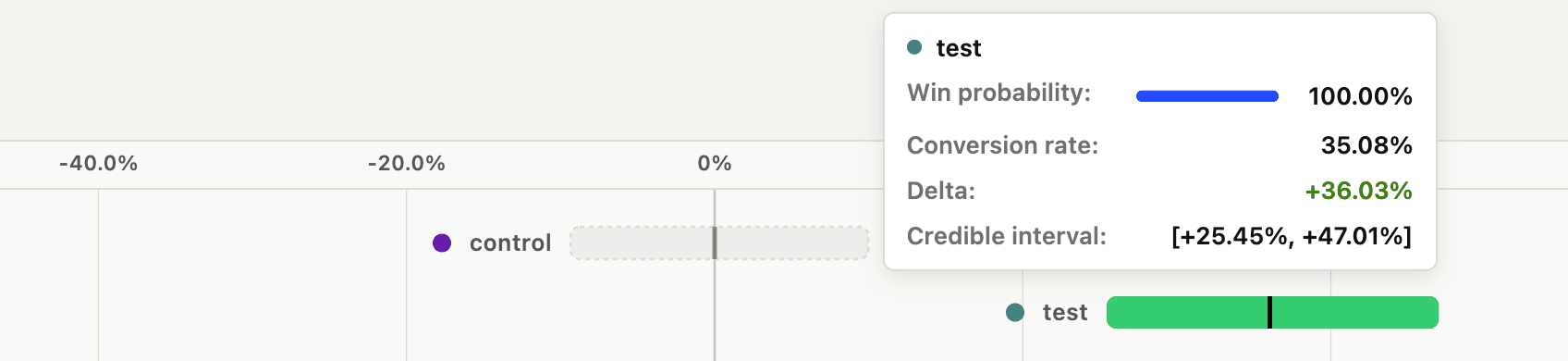

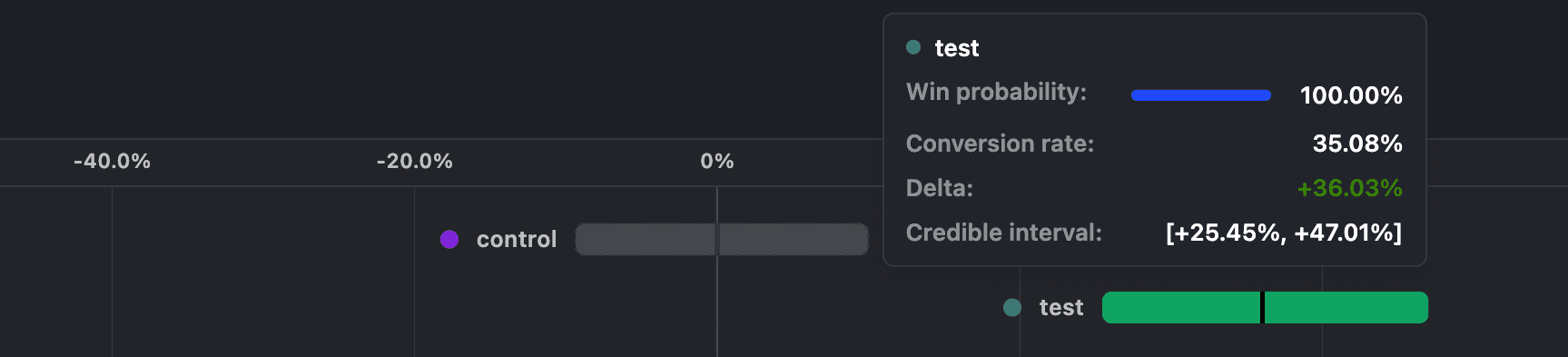

As such, you decide to let the experiment run a bit longer and see these results:

- 304 in 1,179 people in the control group complete the funnel = 25.78% success rate.

- 396 in 1,129 people in the test variant group complete the funnel = 35.08% success rate.

- The control variant has a 0% probability of being better and the test variant has a 100.0% probability of being better.

- The control variant shows a credible interval of [-9.36%, 9.98%] and the test variant shows a credible interval of [25.45%, 47.01%].

Et voilà! The additional data increased the win probability and narrowed the credible intervals. In fact, there's now zero overlap between the credible intervals, which means the test variant is statistically better than the control variant.

With a 100% win probability, you can confidently declare the test variant as the winner. Bayesian statistics let you check your results whenever you'd like because you have win probabilities and credible intervals to help you understand the results.

Supported metric types

Experiments support three different types of metrics, each with a statistical approach appropriate to the shape of its data:

Funnel metrics (like conversion rates)

- Data is always between 0% and 100%.

- Example: Percentage of users who complete a purchase.

- Uses a Beta model.

Count-based trend metrics (like event totals)

- Data is any non-negative whole number (0, 1, 2, etc.).

- Examples: Number of pageviews, button clicks, or form submissions.

- Uses a Gamma-Poisson model.

Value-based trend metrics (like monetary amounts)

- Data can be any number and often has a long tail of high values.

- Examples: Revenue per user, time spent on page.

- Uses a Lognormal model.

If your experiment was created prior to January 2025, it is evaluated using the legacy methodology.